“

The Measure of All Things“ by Ken Alder tells the story of

Pierre Méchain and

Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre’s efforts to survey the line of constant longitude (or meridian) between Dunkerque and Barcelona through Paris, starting amidst the French Revolution in 1792.

The survey of the meridian was part of a scheme to introduce a new, unified system of measures. The idea was to fix the length of the new unit, the metre, as 1/10,000,000th of the distance between the North Pole and the equator on a meridian passing through Paris.

At the time France used an estimated 250,000 different measures across the country with each parish having it’s own (uncalibrated) weights and measures with different measures for different types of material i.e. a “yard” of cotton was different from a “yard” of silk, and different if you were buying wholesale or selling to end users. These measures had evolved over time to suit local needs, but acted to supress trade between communities. Most nations found themselves in a similar situation.

Although the process of measuring the meridian started under the

ancien regime, it continued in revolutionary France as a scheme that united the country. The names associated with the scheme: Laplace, Legrendre, Lavoisier, Cassini, Condorcet, leading lights of the Academie des Sciences, are still well known to scientists today.

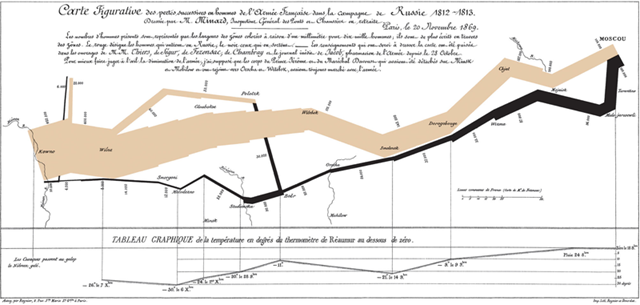

Such surveying measurements are made by

triangulation, a strip of triangles is surveyed along the line of interest. This involves precisely measuring the angles between each each vertex of the triangles in succession: given the three angles of a triangle and the length of one side of the triangle the lengths of the other two sides can be calculated. It’s actually only necessary to measure the length of one side on one triangle on the ground. Once you’ve done that you can use the previously determined lengths for successive triangles. All of France had been surveyed under the direction of César-François Cassini in 1740-80, the meridian survey used a subset of these sites measured at higher precision thanks to the newly invented

Borda repeating circle. As well as this triangulation survey a measure of latitude was made at points along the meridian by examining the stars.

The book captures well the feeling of experimental measurement: the obsession with getting things to match up via different routes; the sick feeling when you realise you’ve made a mistake perhaps never to be reversed; the frustration at staring at pages of scribbles trying to find the mistake; the pleasure in things adding up.

Méchain and Delambre split up to measure the meridian in two sections: Delambre taking the northern section from Dunkerque to Rodez and Méchain the section from Rodez to Barcelona. Méchain delayed endlessly throughout the project, trusting little measurement to his accompanying team. Early on in the process, at Barcelona, he believed he had made a terrible error in measurement, but was unable to check whilst Spain and France were at war. He was wracked by doubt for the following years, only handing over doctored notes with great reluctance at the very end of the project. He was to die not long after the initial measurements were completed, leaving his original notes for Delambre to sift through.

At the time the measurements were originally made the understanding of experimental uncertainty, precision and accuracy were poorly developed. Driven in part by the meridian project and similar survey work by Gauss in Germany, statistical methods for handling experimental error more rigorously were developed not long afterwards. I wrote a little about this back

here. Satellite surveying methods show that the error in the measurement by Méchain and Delambre is equivalent to 0.2 millimetres in a metre or 0.02%.

In the end the Earth turns out not to be a great object on which to base a measurement system: although it’s pretty uniform it isn’t really uniform and this limits the accuracy of your units. The alternative proposed at the time was to base the metre on a pendulum: it was to have the length necessary to produce a pendulum of period 2 seconds. This is also ultimately based on properties of the Earth since the second was defined as a certain fraction of the day (the time the Earth takes to rotate on its axis) and the local gravity which varies slightly from place to place, as Maskelyne

demonstrated.

Following the Revolution, France adopted, for a short time, a decimal system of time as well as metric units but these soon lapsed. However, the new metric units were taken up across the world over the following years - often this was during unification following war and upheaval.

The definition of the basic units used in science is still an active area. The definition of the metre has not relied on a unique physical object since 1960, rather it is defined by a process: the distance light travels in a small moment of time. However, the kilogram is still defined by a physical object but this may end soon with some exquisitely crafted

silicon spheres.

I must admit to being a bit wary of this book in the first instance, how interesting can it be to measure the length of a line? However, it turns out I like to read history through the medium of science and the book provides an insight into France at the Revolution. Furthermore measuring the length of a line is interesting, or it is to a physicist like me.

Thanks to

@beckyfh for recommending it!

Footnotes

1. The full-text of the three volume “

Base du système métrique décimal" written by Delambre is available online. The back of the second volume contains summary tables of all the triangles and a diagram showing their locations.

2. The author’s

website.

3. Some locations in

Google Maps.